The IEC’s decision to appeal the Electoral Court’s order setting aside its own decision to uphold an objection against the candidacy of former president Zuma for the National Assembly has triggered an avalanche of commentary, most of it misleading and mistaken.

As we have previously warned, the fiercely contested nature of these elections counsels against making rash judgements and statements about the Electoral Commission of South Africa’s (IEC) conduct that may undermine its integrity and legitimacy. Unfortunately, our warning has not been heeded.

Two days before candidate lists for the 29 May elections were to be certified by the IEC, in line with the election timetable, the Electoral Court set aside its decision upholding an objection to former president Jacob Zuma’s candidacy based on section 47(1)(e) of the Constitution. It issued an order without reasons, and those reasons are yet to be released.

Without speculating on what those reasons might be, the effect of the order is plainly clear: it is at odds with the IEC’s interpretation of section 47(1)(e). That alone is sufficient for the IEC to seek an appeal because it affects how the IEC will apply the section in future elections.

Yet commentary in these pages and elsewhere has sought to impugn the IEC’s motives as partisan and political. Not only is this unfair on the IEC, it also rests on flawed premises. First, we are told that the IEC’s decision to appeal in the absence of reasons is irrational. That is plainly false. Our law is clear that an appeal lies against an order of a court and not the reasons for the order. In this case, that is clear: whatever reasons the court relied on, the order upsets the IEC’s long-standing interpretation of section 47(1)(e) which it has presumably applied since 1999.

MK party supporters protest outside the Electoral Court in Bloemfontein on 19 March 2024. (Photo: Gallo Images / Volksblad/Mlungisi Louw)

The IEC’s papers in the Constitutional Court also reveal that it is not bringing a brand-new case but is seeking a fresh adjudication before a higher court of the same case it presented to the Electoral Court. That is what the appeal process is for.

Second, the IEC is accused of being biased because it is appealing a judgment that concerns an objection by a third party and not the IEC itself. It is true that the Electoral Act empowers the chief electoral officer to object to the inclusion of a particular candidate on a party list. However, that misses the point.

In upholding the third party objection, the IEC rendered a decision that was informed by its interpretation of the law and it was that decision that was challenged in the Electoral Court. The IEC is then perfectly entitled to appeal that court’s order if it considers it erroneous. Nothing turns on the fact that the objection was not the IEC’s to begin with; the IEC’s exercise of its powers is what is at stake.

Third, it has been argued that members of the Constitutional Court are possibly conflicted, having decided the contempt of court application which led to Zuma’s 15-month sentence and imprisonment. But that objection is also mistaken. The court is not being asked to revisit that decision, only to interpret section 47(1)(e) and to determine whether the IEC applied it correctly. There may be some debate (as there was in court below) about the effect of the remission of sentence granted by President Cyril Ramaphosa on the sentence served by Zuma, but that is also an objective determination based on the law of remission and pardons that has nothing to do with the initial decision to convict and sentence him. Nothing precludes a court from deciding a civil matter that involves a party it had previously convicted and sentenced in a criminal matter.

One commentator has gone so far as to say that the IEC risks “being seen as indirectly stating that the remission of Zuma’s sentence was done by the ANC to meet self-serving ends and did not reflect prudent public policy judgment”. But that is quite a stretch and an unfair criticism that is not borne out by the IEC’s public statements or its court papers. It is unfortunate that these mistaken views appear to be gaining traction with the media and the public.

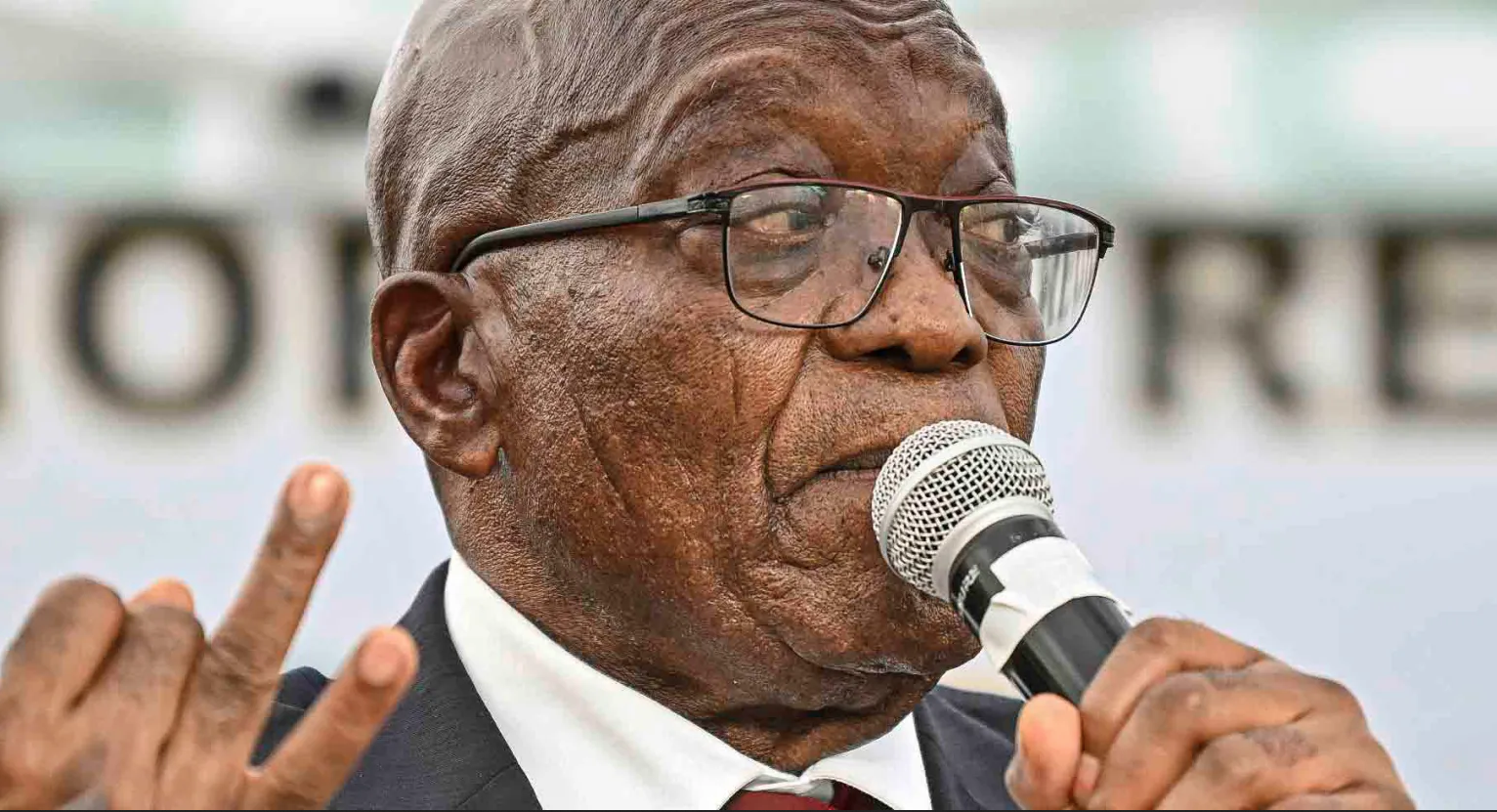

Former president Jacob Zuma addresses supporters outside the Electoral Court in Bloemfontein on 19 March 2024, after the ANC challenged the registration of the MK party by the Electoral Commission of South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Volksblad / Mlungisi Louw)

They are fundamentally misinformed and poison public sentiment against the IEC which is simply discharging its obligation to conduct free and fair elections. In our view, the IEC has prudently sought a final decision from the apex court in order to avoid having a cloud of doubt hanging over Zuma’s eligibility for election to the National Assembly. The idea that this is a question that could be deferred to after the polls is simply folly – it would pose a greater risk to the IEC’s legitimacy were it to attempt to disqualify Zuma from taking office once he has become entitled to do so after the elections.

Perhaps even more absurd is the suggestion that it is the National Assembly’s responsibility to disqualify someone from becoming a member, because the National Assembly would only be able to do so after it is constituted after the elections; after the new members are sworn in, including the potentially disqualified members. It is simply irrational.

We again urge restraint in our public discourse and hope that commentators will be sensitive to the conditions in which the IEC operates and will exercise due care when analysing events as they unfold, always careful not to unjustifiably impugn the IEC’s integrity and independence. DM

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!