“To read the archive is to enter a mortuary; as it permits one final viewing and allows for a last glimpse of persons about to disappear into the slave hold,” wrote Saidiya Hartman, the American scholar in the acclaimed essay Venus in Two Acts. Those who reach into the archive can exhume, terrifyingly, traumatic histories of violence, dispossession and erasure. Through a new exhibition of works by Namibian artists at AVA Gallery in Cape Town, the process of reaching into the archive returns to the surface bodies that were never mourned.

Curated by artist Jo Rogge, Unmourned Bodies sits at the geographical intersections between Namibia and South Africa. Claiming as its nexus, the archive of the Namibian Arts Association (NAA)/ Arts Heritage Trust collection, this exhibition highlights the political and artistic entanglements between the two countries.

Through engaging with the archive, the participating artists were invited to reflect and respond to uncovered histories relating to the conquest of German South-West Africa (Namibia) by South African forces (1914-1915), the German genocide of Herero and Nama people (1904-1908), the historical link between South West African Association of Arts (Swaa) and the South African Association of Arts (Saaa), now The South African National Association for the Visual Arts (Sanava) which is the oldest non-governmental association for visual arts in this country. In this way, the exhibition offers a framework to explore the art landscape and political history of Namibia.

The group of artists who breathed new life into the NAA archive include Maria Caley, Stephanie Conradie, Actofel Ilovu, Ju/’hoansi artists, Tangeni Kambudu, Maria Mbereshu, Tuli Mekondjo, Lynette Musukibili, Ndako Nghipandulwa, Jo Rogge and Rudolf Seibeb. A common thread among them seems to be their use of unconventional materials that upturn traditional mediums such as painting and sculpture.

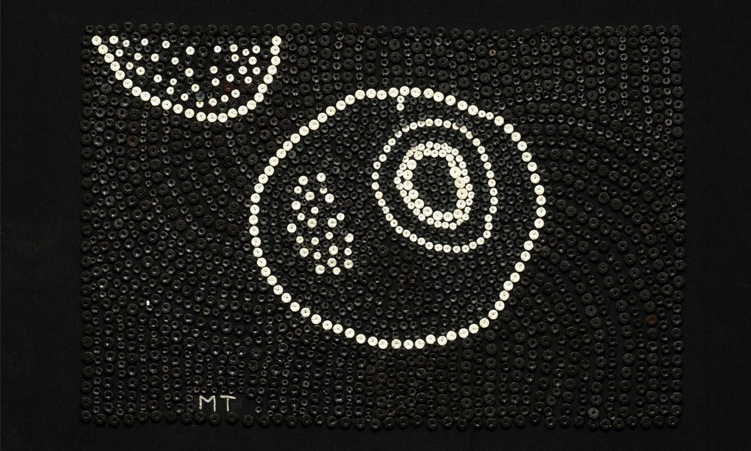

This is driven through the use of natural dyes, Namibian ochre, fabric paint, thread, tulle, cotton, ash, smoke, ostrich eggshell beads, glass, mirror, seeds, makalani, plastic and nails, creating an interesting interplay between hard and soft materials. Works are stitched, glued, sculpted, woven and painted — a testament to the extensive range of expression found in Namibian art. They bring about the questions of how to engage Namibian art, particularly that which is labelled “craft” or “artefact”, in a manner that does not pull the work towards the folkloric and traditional but rather towards the modern and contemporary.

Conversations around archives are fragmentary and incomplete. In academic spaces, archives are discussed in theoretical terms, often beginning with Michel Foucault’s reading of the archive as “the first law of what can be said”, that is to say: a system that governs how events first appear as statements. Similarly, few exhibitions confront the practical implications of archives beyond these abstract terms.

A key practical component, not exclusive to this exhibition, that we have not even begun to speak about is the impact of archives on climate change. In the exhibition catalogue, Rogge notes that “archives are important”. But what does this mean in the context of a warming planet? Another critical question is what is at stake when we use resources to uphold archives that are inherently racist and exclusionary, such as the NAA archive in terms of its depiction of indigenous peoples and their cultures.

In a conversation with academic Patricia Hayes, the curator relayed an anecdote of the difficulty of ascribing authorship and ascertaining details regarding historical works in the Arts Heritage Collection, pointing to absences and erasures of San artistic contributions to the art historical canon. The inclusion of works by artists of Ju/’hoansi origins — a population of Khoisan-speaking hunter-gathers residing in northeastern Namibia and the northwestern region of Botswana — makes for an exhibition that traces art-making practices today to its earliest iterations. Made from Ostrich eggshell beads, these works depict geometric forms and patterns believed to contain narratives, guidance and council.

Namibian-born and Cape Town-based Stephanie Conradie’s dramatic assemblages convert fragments, scraps and leftover mugs, jugs, cups and other household articles into unfamiliar objects that require considered looking.

Caley’s work is held precariously in place by threads. The artist draws from her background as a designer and adds a fragile tactility to the exhibition. Mekondjo’s ancestral figurines are reminiscent of the Ambo Ovambo fertility dolls while the use of earthly substances of ochre and soil reflect the land. The influence of incredible Namibian artists such as Papa Shikongeni, Joseph Madisia and John Muafangejo is discernible in the work of Rudolf Seibeb.

Seibeb uses a common style of rendering where figures are stacked tightly together leveraging flatness and two-dimensionality.

Muafangejo, whose primary medium was linocut, received international acclaim for his expressive and emotive artworks. He studied at the Arts and Craft Centre of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Rorke’s Drift, Natal in South Africa, which played a significant role in the development of the art landscape in the country with an alumnus including; Allina Ndebele, Jessie Dlamini, Dan Rakgoathe, Azaria Mbatha, Cyprian Shilakoe and Vuminkosi Zulu. These connections highlight the convergences and influences between artists in the Southern African region.

Returning to the archive is in some ways akin to what Fred Moten speaks of as staying in the hold — a place of terror. By staying in the hold we might be able to uncover emancipated knowledge, a kind of knowledge that allows us to understand our roots better and moves us towards change in practical ways, speaking to Karl Marx’s assertion that to know oneself in a new way is to alter oneself in that very act. The artist’s engagement with a problematic archive can therefore be read as one way to create emancipatory knowledge.

If we think of the archive as a process of collecting and ordering Unmourned Bodies is a reordering, a communal ascension that allows artists to speak back to silenced histories hidden in the dark rooms of archives — a claiming back of bodies and spirits forgotten and unaccounted for.

It is a reminder that the work of historical excavation is murky, at once troubling and invigorating as it allows a deeper reflection on the aesthetic, historical and emotional value of objects we create to tell our stories. DM/ ML

This text was produced during an independent journalism development project by African Arts Content focused on the Church Street art node in Cape Town.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!