AmaBhungane managing partner Sam Sole delivered a keynote Q&A this week at Engage SA, an anti-money laundering conference attended by banks, risk professionals and other compliance specialists, including the Financial Intelligence Centre.

You have nearly 40 years as a journalist. How did your career progress into you becoming an investigative journalist and forming amaBhungane?

Well, I suppose I am a frustrated policeman. Growing up under Apartheid meant that becoming a cop was never on the cards as the police represented the sharp end of an unjust system. However, journalism offered a way to expose injustice and abuses of power. I started doing investigative journalism before it was really a ‘thing’ – I just gravitated towards ‘news you are not supposed to know’. That was formalised when I joined the Mail & Guardian newspaper’s investigative team in around 2001. My co-founder Stefaans Brummer and I wanted to do more and the M&G didn’t have the resources, so we spun the investigating unit off into a nonprofit company that continued to be funded by the newspaper but could also raise donor funding. In 2016 we split completely from the M&G and are now 100% donor funded, partly via crowdfunding.

State capture appears to be a huge issue in South Africa. It is mentioned several times in the recent Financial Action Task Force (FATF) report about the reason for SA’s greylisting. What are you seeing, how extensive is corruption still in South Africa?

The greylisting is merely symptomatic. I am not optimistic about progress.

Corruption is endemic and organised crime and violence is gaining a stronger and stronger foothold. This was graphically demonstrated by the assassination of Cloete Murray and his son.

The core problem is that we have witnessed the collapse of the formal accountability institutions of the state: the police, the Hawks, the National Prosecuting Authority.

This collapse is at the heart of why we have been greylisted. In this regard, FATF found that South Africa has a solid legal framework for combating money laundering and terrorist financing, but significant shortcomings in implementation.

What are the key ways state capture is occuring in South Africa today?

We need to understand that state capture involved two related processes. The one we mostly think of relates to the enormous influence the Gupta family were able to exercise over certain state processes because of their ‘capture’ of the president and his family and allies. Through this they were able to redirect key contracts – mainly in the State Owned Enterprises – from which they profited either directly or via offshore commissions such as those paid by the Chinese locomotive manufacturers.

However, the second, perhaps more important aspect of state capture was the earlier project, more directly controlled by the President, to seize formal and informal control of the criminal justice system and the intelligence services (including via their politicisation and de-professionalisation) in order to create a system of impunity for himself and his faction.

Those systems are still broken.

Perhaps the most visceral indicator is that, since 2012, the ability of the SAPS to solve murders has dropped by 55% – it has more than halved. In the 2021/22 financial year, this was reflected in the fact that only 14.5% of murder cases were closed as ‘detected’.

The ability of the SAPS and the NPA to investigate and prosecute complex financial crime is now almost non-existent.

The weakness of the presentation in the first ‘seminal’ state capture Gupta case – the Nulane prosecution – and the abject failure of efforts to extradite the Guptas is evidence of this terrifying loss of skills, capacity and will.

If any of you have read Jacques Pauw’s latest book, In the Shadow of the President’s Keepers, you will appreciate that while some of the leadership in these entities has been replaced, a frightening number of tainted police, prosecutors and intelligence officials who were appointed or promoted during the state capture era are still in place.

The inability of the state to police its own processes is a key factor in the situation we find ourselves in, because the state is seen as the key site of self-enrichment, patronage and accumulation of power.

This takes place at every level, including local, provincial, and national government as well as the state-owned enterprises. Many political parties, if not all, are tied into this process as a way of accumulating funds and support. Many businesses are also connected to these networks, and various middlemen sell their ability to manage or manipulate the process, even to ‘respectable’ businesses. This is a vicious and self-reenforcing circle.

The way in which procurement processes were massively abused during the Covid-19 emergency is testimony to how entrenched this corruption is.

Who is involved in state capture and how does this, if at all, link to international organised crime?

To answer this I am going to draw on brief paper given by the late Stephen Ellis, a former editor of Africa Confidential, who was one of the foremost researchers on organised crime in Africa.

He isolates three main themes.

1. The merging of politics with crime. The end of the Cold War 25 years ago was crucial in this regard. Political elites and secret services with no ingrained respect for law made common cause with existing crime barons in a profound reconfiguration of power in the former Soviet bloc. But even in the great democracies, where respect for law is strong, the relationship between politics and crime has changed. Part of the reason is that political campaigning has become far more expensive, requiring politicians to raise colossal sums of money – far more than they could hope to receive from individual subscriptions or even from corporations seeking access to future governments. Politicians may have recourse to contributions from people or businesses engaged in illegal activity who are prepared to make exceptionally large campaign contributions because they require political protection. Incumbent politicians may make arrangements with certain companies (oil companies and arms companies especially) to provide them with slush funds in return for political favours.

2. Financial globalisation and the adoption of free market economics. This has permitted huge international transfers of money that are hard or impossible to regulate. Criminal markets that until quite recently small and isolated, have become integrated into the legal economy, creating an overlap between legitimate and criminal business, or rather a grey area where they become difficult to distinguish from each other. Financial deregulation has enormously increased the scope and profitability of transnational organized crime. It is estimated that between 2001 and 2010, developing countries lost no less than US$5.86 trillion to illicit outflows. Just as transfer pricing is an invoicing technique used by multinational companies to switch funds between jurisdictions, people exporting money illegally from the developing world use a similar approach according to the main research organisation in this field, Global Financial Integrity, which reports that about 80 percent of illicit outflows in recent years have been channeled through the deliberate mis-invoicing of trade.

3. A connection between the types of crime characteristic of failing states and high finance in rich countries. Both are associated with the offshore world, where business turns to criminal behaviour and organised crime tries to become legitimate. Considered from a global perspective, the resulting system can be analysed in terms of sovereignty and anti-sovereignty. Legitimate businesses in leading states need the services of anti-sovereign spaces when they wish to conduct operations of dubious legality. This includes, notably, channelling funds offshore so as to minimise their tax obligations, but also other types of activity, such as when a leading bank wishes to finance an arms deal or evade a sanctions regime. At the same time, large criminal organisations thrive in anti-sovereign spaces. Entrepreneurs who have made money in such countries need to have access to better-established sovereign states in order to launder their money effectively, for example by by depositing funds in major banks in world-class financial centers like New York or London. In short, a fundamental shift in the way the world works has in turn transformed the relationship between politics and crime and has led to a change in the nature of grand corruption. There has been an increase not only in the scale of corruption and fraud in this sense, but above all an enhancement of its strategic importance.

Is state capture in South Africa just a South African problem?

South Africa is quite significant for containing the elements of a weakened state that allows for organised criminal activity to flourish while simultaneously sustaining a sophisticated commercial legal and financial infrastructure that allows for the proceeds of that criminal activity to be laundered easily into the licit economy.

Put more clearly: the boss who controls the syndicate that hijacks your wife when she drops the children off at school probably has an account at your bank.

We should not fool ourselves into thinking this is just a South African phenomenon.

The social contract that sustains meaningful representative politics has been corrupted globally via the massive encroachment of money and mafias into the political process.

Looking at at Donald Trump, it could be argued that he followed a trail blazed by former president Jacob Zuma.

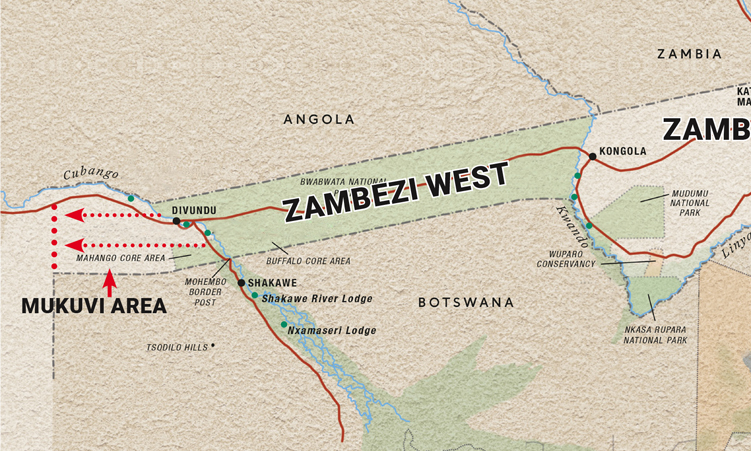

And of course we are learning that the mafia state that is Zimbabwe spills more and more across our borders. Organised groups of people who have made asset stripping, grand corruption and money laundering an established feature of the state they run are starting to look for new markets.

Can you share some observations on recent investigations you have been involved with?

The GuptaLeaks investigations were a good example of some of the global features I have been talking about. The Guptas were quite crude corruptors, but they were highly sophisticated money launderers, in part because they made use of existing laundry networks in South Africa, Dubai and Hong Kong. The movement of money through myriad accounts out of and back into the country, and the use of financial cutouts such as fixed deposit backed loans, is part of the reason our criminal investigators have been left befuddled.

However, it is also notable that, notwithstanding their crude and overt influence peddling, there was a line of multinationals, from McKinsey to SAP – and including some banks and audit firms – that queued up to profit from the corrupt influence that the Guptas were able to wield.

I also want to highlight the more recent work we did on the attempted takeover of Tongaat Hulett, where an entity controlled by the Rudland family of Zimbabwe very nearly laundered a couple of billion rands into one of our most venerable listed companies.

Here I should emphasise that despite the very clear red flags that we pointed out at the time – and which have been amply confirmed by the recent Al Jazeera series on the so-called Zimbabwean gold mafia – this transaction was given a clean bill of health by a major South African bank as well an established audit firm.

You are presenting to an audience of financial crime professionals representing most of the financial institutions in South Africa. What can they do to help fight corruption?

A lot more.

We are on a downward spiral and it is going to take a ‘whole of society’ approach to turn things around, so I really want you to ask yourselves: what is the responsibility of banks, auditors and risk professionals when they are operating in a country sliding towards becoming a failed state?

What is your role?

It cannot be business as usual.

Banks have a key interest in restoring a rule-based system where debts are paid and disputes are settled with lawyers rather than bullets.

That means getting real about the failing state and its failing institutions, and being prepared to adopt a less blinkered, less comfortable approach to policy and to partnerships, including with civil society and the media.

I’ll give you an example of what I mean.

During the riots that took place in KwaZulu Natal and Gauteng in July 2021, among the most visibly sophisticated and coordinated conduct was the attack on banks and ATMs.

According to a press statement issued by the South African Banking Risk Information Centre (SABRIC), ATMs and bank branches lost R119,400,243 in cash. Between 9-17 July, at least 1,227 ATMs and 310 bank branches were vandalised or destroyed in the unrest.

As investigative journalists we were interested in finding threads that might lead back to the instigators of this hugely destructive event, and given the nature of the assault on the banks we thought this would be the best place to look for those threads.

We approached SABRIC and asked to sit down with them to compare notes, establish what video footage they had and determine whether they had managed to pool information from members around the country in order to establish a precise timeline of events.

They wouldn’t even have an exploratory meeting with us and were content to say that they had handed their information over to the Hawks.

In the current milieu, that attitude is dangerously shortsighted.

The situation demands that some of the good actors step up and display some of the same agility and willingness to take risks that propels the bad actors.

That may mean building networks of trust outside of your comfort zone.

It may mean you have to countenance providing ‘leaks’. If a former constitutional court judge like Edwin Cameron can do it in the Thabo Bester case, perhaps the odd banker can too.

It also means creating the structures and processes to enable information sharing and risk assessment among peers, and working out a common legal position to ensure that this does not fall foul of competition rules. Cooperation in respect of anti-money laundering and anti-fraud measures arguably cannot and should not be construed as collusion in the market.

Finally, it also means adopting a much more radical policy approach towards transparency in respect of, for instance, public sector and private sector procurement, tax compliance and disclosure of beneficial ownership.

These are some of the tings that FATF demanded, but government and the private sector are still resistant to public disclosure and instead favour disclosure only to ‘competent authorities’.

Has the recent addition of South Africa to the greylist changed the status quo? What more needs to be done to fight state capture that isn’t already being done?

I think because of the capacity constraints within the state and the perverse situation that sees political parties and factions benefiting from some of these abuses, the measures to address the shortcomings that led to greylisting risk being symbolic box-ticking exercises.

That said, the issue has focused government’s mind on some of the policy issues around transparency and procurement, but I think the private sector needs to do more.

The last press release on the Business Against Crime website is from June 2021, just before the unrest. I see that as emblematic of where we are.

Reaching consensus around some core interventions that business can make is key.

The state is broken, but we dare not abandon the state. There is no gated community with walls high enough.

Indeed, some of the most successful gangsters are probably your neighbours. –AmaBhungane

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!