The Tsau //Khaeb National Park is Namibia’s most biodiverse park, and it has been virtually untouched by humans for more than a century – it was the ‘forbidden zone’, the Sperrgebiet, to secure the area’s diamonds. Now a German company has been given the go-ahead for a huge hydrogen development in the park.

The twin global crises of climate change and biodiversity need to be addressed simultaneously and, as far as possible, in complementary ways. The current proposal to produce “green” hydrogen by turning a near-pristine global biodiversity hotspot in Namibia into an industrial site is certainly not the way forward.

The Namibian Chamber of Environment’s recent position paper, launched on International Biodiversity Day, argues that any hydrogen produced at the expense of biodiversity is more correctly termed “red hydrogen”.

What ‘green’ hydrogen production entails

The term “green hydrogen” was coined to describe hydrogen production using 100% renewable energy, such as wind and solar power. The process of capturing the energy from these natural resources involves hundreds of huge wind turbines and solar panels, which have a number of environmental impacts. Plants under the solar panels that are adapted to full-sun desert conditions will not survive, while the massive turbine blades are known to kill birds and bats.

These direct impacts are concerning, yet they are among the least of our worries. The solar farms and turbine arrays all require roads, transmission lines and other infrastructure for maintenance and electricity distribution (powerlines are worse news for birds such as the endangered Ludwig’s bustard than turbines).

Producing the hydrogen requires a desalination plant, while converting hydrogen to ammonia requires another industrial plant. In short, the area used for such a project will be turned into a light industry zone with all the attendant environmental impacts.

If all of the above developments were planned for inland parts of southern Namibia where farming is increasingly difficult and biodiversity is relatively poor, the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) would fully support these plans.

Yet the proponent of this project – Hyphen Hydrogen Energy – has been allocated the worst possible location by the Namibian government in terms of biodiversity conservation.

What’s at stake: a global biodiversity hotspot

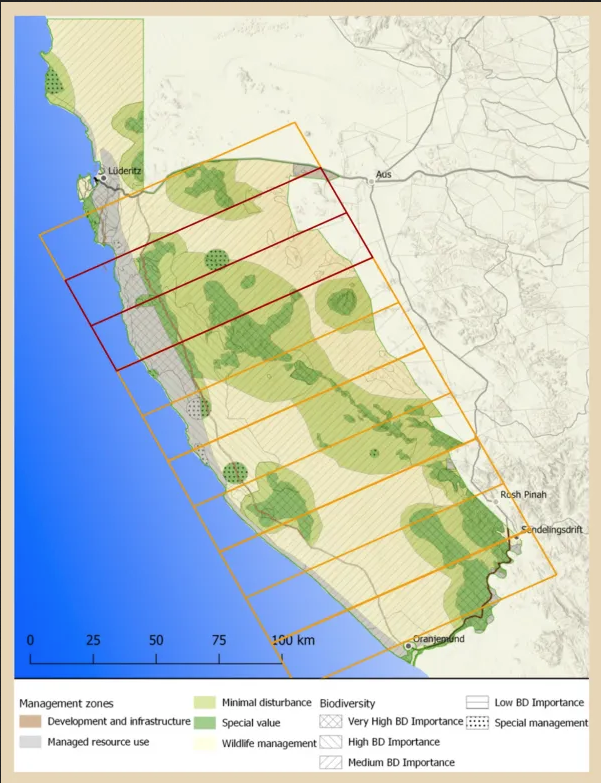

The Tsau //Khaeb (formerly Sperrgebiet) National Park is Namibia’s most biodiverse park, and most of it has been virtually untouched by humans for more than a century. This area was initially protected as the “forbidden zone” (Sperrgebiet) to secure the extensive diamond deposits in the area. While diamond mining took place along the coast and has now largely moved offshore, 70% of the 21,800km2 park remains entirely undeveloped.

The habitat in this area is part of the Succulent Karoo Biome – one of few global biodiversity hotspots in an arid area – which Namibia shares with South Africa.

While this national park is important for all forms of biodiversity, its plant diversity is nothing short of spectacular. Covering only 3% of Namibia’s land area, Tsau //Khaeb hosts 25% of the country’s plant species, including 31 that occur nowhere else on Earth (known as endemic).

As the park attracts more research attention it is likely that many more endemic species will be discovered, especially reptiles and invertebrates.

A comprehensive park management plan completed in 2020 envisaged low-impact, carefully guided tourism as the only kind of development that would be compatible with this extremely sensitive environment.

If the environmental costs that will be borne by Namibia for this project were transferred to Germany, would their voting public support it?

Building a lodge on a particular hill or koppie could result in the extinction of an entire plant species, while any cleared areas would take decades or more to rehabilitate. Transplanting is unlikely to work for many species, while rehabilitation efforts by the mines have achieved mixed success. Some areas will simply never recover once disturbed.

While the Hyphen concession area already covers 4,000km2, the Namibian government has stipulated that this project must develop enough infrastructure to facilitate several others like it in future. The long-term picture presented by Hyphen and the government shows the entire park zoned for hydrogen development.

The impacts of the current and long-term plans will extend beyond the project site to the coastal areas. Ammonia and desalination plants are planned for a peninsula near Lüderitz that is part of an Important Bird Area and a key tourist attraction.

This relatively unspoiled part of the coast includes a number of small islands that critically endangered and endangered seabirds use as roosting and breeding sites. This coastline and its associated marine ecosystem are part of the Namibian Islands Marine Protected Area – the only one of its kind in Namibia.

The larger plans for industrialisation of Lüderitz (including but not limited to large-scale hydrogen development) involve the construction of a deep-sea port on this peninsula to service the many ships that will be exporting Namibia’s products to the world. The development of the port, increased shipping activity and associated industrial activities will most likely force birds and tourists to go elsewhere.

Germany’s schizophrenic approach to conservation, climate change and energy

The park management plan that recommended low-impact development to limit biodiversity loss and ecosystem damage was funded by the German government through its development bank, KfW. Ironically, the same German government is now throwing its weight behind the Hyphen project and future hydrogen development projects in the same area.

If the environmental costs that will be borne by Namibia for this project were transferred to Germany, would their voting public support it? The near pristine parts of the Tsau //Khaeb National Park cover a larger area than seven of Germany’s largest protected areas combined, and none of those are even close to pristine or of global biodiversity importance.

If the industries in Germany find out that they are paying top dollar for red hydrogen rather than the promised green hydrogen… Namibia will be left with a huge white elephant.

Indeed, this near-pristine area is four times larger than all of the recognised wilderness areas in the European Union combined. Would Europe be willing to sacrifice its little remaining wilderness for the sake of “green” energy production?

While the Namibian government thinks that it has hit the jackpot with “green” hydrogen, it is really bearing the environmental cost of Germany’s energy needs. While the German population is unwilling to live with nuclear reactors due to safety and environmental concerns, they were happily importing gas and coal from Russia – thus switching from a relatively clean, reliable source of energy to a dirty, unreliable one.

The Ukraine-Russia war exposed the vulnerability of German reliance on Russian gas, sparking a search for “greener” sources of energy without returning to nuclear power or increasing the use of fossil fuels.

The costs and risks borne by Namibia

Hydrogen and its derivatives – ammonia and kerosene – have been touted as part of the solution to the energy problem, particularly “green” versions that are produced from renewable energy.

There is one major hitch, however. These products are considerably more expensive than those produced using non-renewable energy. The price of “green” hydrogen can be reduced somewhat by siting production plants in an area with near constant sunlight, frequent windy conditions, a large amount of water and nearby harbour for export – a description that neatly matches the Tsau //Khaeb National Park south of Lüderitz.

Yet hydrogen produced from this area will come with massive environmental costs, pushing many species into the red (towards extinction) and dripping with the metaphorical blood of Namibia’s biodiversity.

This red hydrogen will still be more expensive than “dirty” hydrogen produced from non-renewable energy sources. Since the whole project relies on a market that is willing to pay a premium for something that is environmentally friendly, Namibia’s dreams of hydrogen-driven prosperity are on very shaky ground.

If the industries in Germany find out that they are paying top dollar for red hydrogen rather than the promised green hydrogen, or if the world simply finds cheaper sources of clean energy in future, Namibia will be left with a huge white elephant. The promised jobs and economic prosperity will turn to dust, with no more to show for it than an irretrievably damaged national park that has lost its tourism appeal and potential for sustainable development.

Standing up for Namibia’s environment and sustainable development

The NCE, on behalf of our 77 members in the Namibian environmental sector, is in favour of sustainable development projects that are likely to reap high economic benefits for the maximum number of people with the minimum possible environmental cost. This is in line with the constitution and National Development Plans.

The NCE’s stance against red hydrogen development is based on our understanding of the biodiversity value of the area and the risks associated with a fickle export market for the final product.

We therefore recommend that hydrogen development plans be subject to a thorough, transparent strategic environmental and social assessment at the national level, not for a pre-selected region, that considers the full costs and benefits of producing hydrogen.

Given the high costs associated with the proposed location in a hyper-diverse national park, we believe that hydrogen development in other parts of the country will have a much higher benefit-to-cost ratio.

Germany’s investment in Namibia’s national parks, including Tsau //Khaeb, was much needed and highly appreciated. Yet their taxpayers’ money will be entirely wasted if these hydrogen development plans go ahead.

Meanwhile, Namibians who are hoping for jobs and economic development from this project may see little of either if export markets shift to more promising forms of energy, leaving one of the world’s most important national parks as a wasteland with no future tourism potential and jobs.

Namibian, German and global citizens should therefore take a stand against this red hydrogen project and any others that promise to mitigate climate change at the expense of biodiversity.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!