The man who walked out into the rain in Dhaka hadn’t seen the sun in more than five years.

Even on a cloudy day, his eyes struggled to adjust after half a decade locked in a dimly lit room, where his days had been spent listening to the whirr of industrial fans and the screams of the tortured.

Standing on the street, he struggled to remember his sister’s telephone number.

More than 200km away, that same sister was reading about the men emerging from a reported detention facility in Bangladesh’s infamous military intelligence headquarters, known as Aynaghor, or “House of Mirrors”.

They were men who had allegedly been “disappeared” under the increasingly autocratic rule of Sheikh Hasina – largely critics of the government who were there one day, and gone the next.

But Sheikh Hasina had now fled the country, unseated by student-led protests, and these men were being released.

In a remote corner of Bangladesh, the young woman staring at her computer wondered if her brother – whose funeral they had held just two years ago, after every avenue to uncover his whereabouts proved fruitless – might be among them?

The day Michael Chakma was forcefully bundled into a car and blindfolded by a group of burly men in April 2019 in Dhaka, he thought it was the end.

He had come to authorities’ attention after years of campaigning for the rights of the people of Bangladesh’s south-eastern Chittagong Hill region – a Buddhist group which makes up just 2% of Bangladesh’s 170m-strong, mostly Muslim population.

He had, according to rights group Amnesty International, been staunchly vocal against abuses committed by the military in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and has campaigned for an end to military rule in the region.

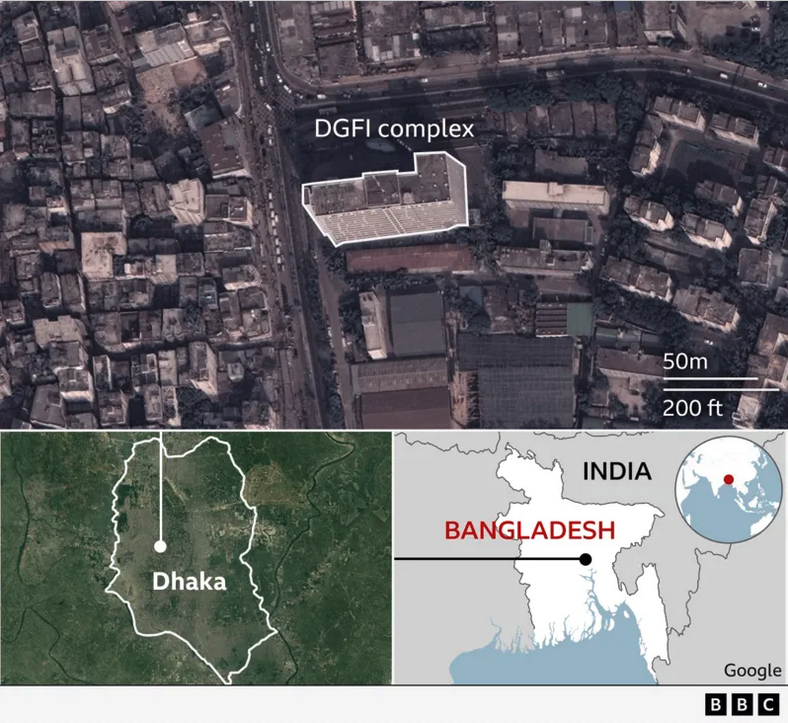

A day after he was abducted, he was thrown into a cell inside the House of Mirrors, a building hidden inside the compound the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI) used in the capital Dhaka.

It was here they gathered local and foreign intelligence, but it would become known as somewhere far more sinister.

The small cell he was kept in, he said, had no windows and no sunlight, only two roaring exhaust fans.

After a while “you lose the sense of time and day”, he recalls.

“I used to hear the cries of other prisoners, though I could not see them, their howling was terrifying.”

The cries, as he would come to know himself, came from his fellow inmates – many of whom were also being interrogated.

“They would tie me to a chair and rotate it very fast. Often, they threatened to electrocute me. They asked why I was criticising Ms Hasina,” Mr Chakma says.

Outside the detention facility, for Minti Chakma the shock of her brother’s disappearance was being replaced with panic.

“We went to several police stations to enquire, but they said they had no information on him and he was not in their custody,” she recalls. “Months passed and we started getting panicky. My father was also getting unwell.”

A massive campaign was launched to find Michael, and Minti filed a writ petition in the High Court in 2020.

Nothing brought any answers.

“The whole family went through a lot of trauma and agony. It was terrible not knowing the whereabouts of my brother,” she says.

Then in August 2020, Michael’s father died during Covid. Some 18 months later, the family decided that Michael must have died as well.

“We gave up hope,” Minti says, simply. “So as per our Buddhist tradition we decided to do hold his funeral so that the soul can be freed from his body. With a heavy heart we did that. We all cried a lot.”

Rights groups in Bangladesh say they have documented about 600 cases of alleged enforced disappearances since 2009, the year Sheikh Hasina was elected.

In the years that followed, Sheikh Hasina’s government would be accused of targeting their critics and dissenters in an attempt to stifle any dissent which posed a threat to their rule – an accusation she and the government always denied.

Some of the so-called disappeared were eventually released or produced in court, others were found dead. Human Rights Watch says nearly 100 people remain missing.

Rumours of secret prisons run by various Bangladeshi security agencies circulated among families and friends. Minti watched videos detailing the disappearances, praying her brother was in custody somewhere.

But the existence of such a facility in the capital was only revealed following an investigation by Netra News in May 2022.

The report found it was inside the Dhaka military encampment, right in the heart of the city. It also managed to get hold of first-hand accounts from inside the building – many of which tally with Michael’s description of being held in a cell without sunlight.

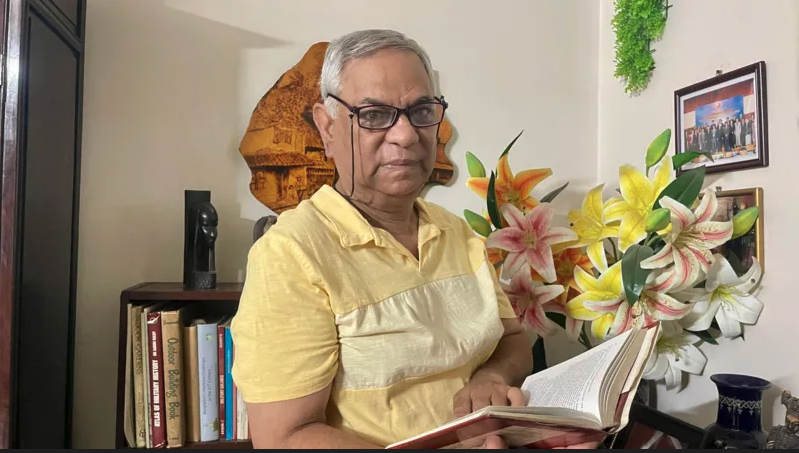

The descriptions also echo those of Maroof Zaman, a former Bangladeshi ambassador to Qatar and Vietnam, who was first detained in the House of Mirrors in December 2017.

His interview with the BBC is one of the few times he has spoken of his 15-month ordeal: as part of his release, he agreed with officials not to speak publicly.

Like others who have spoken of what happened behind the complex’s walls, he was fearful of what might happen if he did. The detainee who spoke openly to Netra News in 2022 only did so because he was no longer in Bangladesh.

Maroof Zaman has only felt safe to speak out since Sheikh Hasina fled – and her government collapsed – on 5 August.

He describes how he too was held in a room without sunlight, while two noisy exhaust fans drowned out any sound coming from outside.

The focus of his interrogations were on the articles he had written alleging corruption at the heart of government. Why, the men wanted to know, was he writing articles alleging “unequal agreements” signed with India by Ms Hasina, that favoured Delhi.

“For the first four-and-a-half months, it was like a death zone,” he says. “I was constantly beaten, kicked and threatened at gunpoint. It was unbearable, I thought only death will free me from this torture.”

But unlike Michael, he was moved to a different building.

“For the first time in months I heard the sound of the birds. Oh, it was so good, I cannot describe that feeling,” Maroof recounted.

He was eventually released following a campaign by his daughters and supporters in late March 2019 – a month before Michael found himself thrown into a cell.

Few believe that enforced disappearances and extra-judicial killings could have been carried out without the knowledge of the top leadership.

But while people like Mr Chakma were languishing in secret jails for years, Ms Hasina, her ministers and her international affairs advisor Gowher Rizvi were flatly rejecting allegations of abductions.

Ms Hasina’s son, Sajeed Wazed Joy, has continued to reject the allegations, instead turning the blame on “some of our law enforcement leadership [who] acted beyond the law”.

“I absolutely agree that it’s completely illegal. I believe that those orders did not come from the top. I had no knowledge of this. I am shocked to hear it myself,” he told the BBC.

There are those who raise their eyebrows at the denial.

Alongside Michael, far higher profile people emerged from the House of Mirrors – including two senior members of the Islamist political party Jamaat-e-Islami, a retired brigadier, Abdullahi Aman Azmi and Barrist Ahmed Bin Quasem. Both had spent about eight years in secret incarceration.

What is clear is that the re-emergence of people like the politicians, and Michael, shows “the urgency for the new authorities in Bangladesh to order and ensure that the security forces to disclose all places of detention and account for those who have been missing”, according to Ravina Shamdasani, a spokesperson for the UN Human Rights office in Geneva.

Bangladesh’s interim government agreed: earlier this week, it established a five-member commission to investigate cases of enforced disappearances by security agencies during Ms Hasina’s rule since 2009.

And those who have survived the ordeal want justice.

“We want the perpetrators to be punished. All the victims and their families should be compensated,” Maroof Zaman said.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!