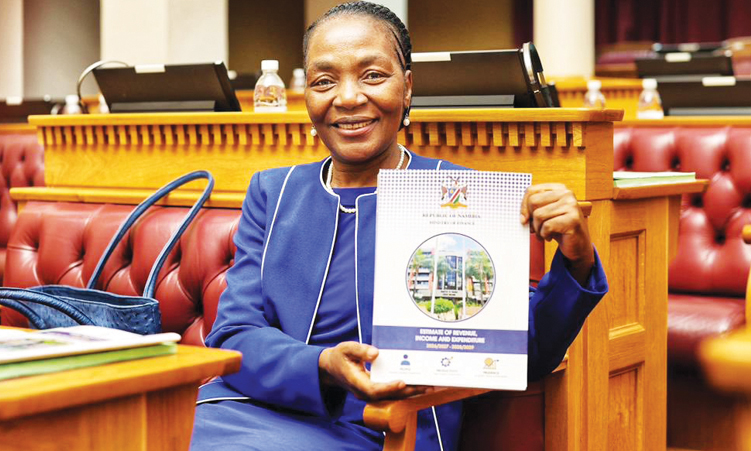

WHEN PRESIDENT NETUMBO Nandi-Ndaitwah announced in parliament that tertiary education would become “100% subsidised by the government” from 2026, the declaration was widely welcomed. For many Namibians, it appeared to signal the long-awaited realisation of the “fees must fall” campaign and a decisive shift towards expanded access to higher education.

Yet, as with many ambitious public policy pronouncements, the substance lies beyond the headline. In this case, the distinction between aspiration and implementation carries significant consequences for thousands of students.

The government has since clarified that the policy does not introduce free tertiary education in the literal sense, but rather subsidised education. This distinction is not semantic; it is foundational.

Under the new framework, tuition and registration fees for eligible undergraduate students will be fully subsidised, with government paying institutions directly. However, students remain responsible for accommodation, transport, textbooks, meals, and learning materials.

To cushion these costs, the Namibia Students Financial Assistance Fund (NSFAF) will offer a non-tuition loan of up to N$17 000 to qualifying needy students.

Clarity on this point is essential. Conflating subsidy with full cost coverage risks inflating expectations and undermining informed public debate.

The policy’s real impact emerges when eligibility criteria are examined. Only first-time undergraduate and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) students pursuing a primary qualification at national qualification framework (NQF) levels 5 to 8 qualify for subsidised fees. Continuing NSFAF beneficiaries who meet the new criteria will transition into the subsidy regime from 2026, while those who do not will remain under existing loan agreements. Postgraduate studies are explicitly excluded.

At the same time, NSFAF has tightened academic and financial thresholds, including higher minimum points requirements and the closure of pathways that previously allowed Grade 11 pupils to access degree programmes. These measures will, by design, exclude a substantial number of students, not necessarily for lack of ability or ambition, but for falling outside revised criteria.

This raises a necessary question: what problem was the policy intended to solve?

If the objective was to remove financial barriers to access, then narrowing eligibility risks reproducing exclusion under a different model. If the concern was rising student debt and the sustainability of the loan system, then that problem should be stated plainly and addressed transparently. Without a clearly articulated problem statement and measurable objectives, it becomes difficult to assess whether subsidisation meaningfully improves access or merely reallocates limited support.

For those who fall outside the new framework, the consequences are tangible. Students who narrowly miss academic cut-offs may find themselves without support altogether. Those pursuing second qualifications or postgraduate studies, often critical for professional development and national skills needs, are excluded from subsidisation. Existing NSFAF debts remain enforceable, meaning historical financial burdens are not relieved by the transition.

Rather than broadening opportunity, the risk is the emergence of a tiered system in which access is redistributed rather than expanded.

There is also a broader fiscal dimension. Early indications suggest government expenditure on tertiary education under the subsidisation model may be lower than under a more expansive loan-based system, given the tightened eligibility and exclusions.

Fiscal sustainability is a legitimate concern, but it should be acknowledged openly. Cost containment, if that is a policy objective, should not be presented as universal access.

For subsidised tertiary education to achieve its stated aims, several elements are essential. First, the government must be explicit about intent: whether the priority is universal access, targeted equity, or fiscal consolidation. Second, transparency is critical. Data on projected beneficiaries and excluded cohorts should be made public to support trust and accountability.

Third, alternative access pathways, including bridging and remedial programmes, must be strengthened to prevent systemic exclusion. Finally, policy thinking must extend beyond first qualifications to include postgraduate study and lifelong learning, both central to a competitive knowledge economy.

Subsidised tertiary education represents a significant policy shift and an opportunity to recalibrate Namibia’s higher education system. Its success, however, will be judged not by announcement, but by outcomes.

If eligibility rules and administrative thresholds exclude substantial numbers of capable students, Namibia risks repackaging an old challenge in new language.

Subsidised is not synonymous with free, and education policy must ultimately be measured by how fairly, broadly and sustainably it serves the national interest.

*Timo Neisho is an information technology professional and public commentator on technology, education and public policy. The views expressed here are his own.

In an age of information overload, Sunrise is The Namibian’s morning briefing, delivered at 6h00 from Monday to Friday. It offers a curated rundown of the most important stories from the past 24 hours – occasionally with a light, witty touch. It’s an essential way to stay informed. Subscribe and join our newsletter community.

The Namibian uses AI tools to assist with improved quality, accuracy and efficiency, while maintaining editorial oversight and journalistic integrity.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!