Filette Uwase spent most of her young life playing with her favourite doll.

She loved rice and chips and was daddy’s “good girl”.

She was two when she was killed in the Rwanda genocide of 1994.

The cause of death on an inscription below her picture in the Genocide Memorial Museum simply reads: “Smashed against a wall.”

Filette’s picture, in her baby clothes, is among the images that brings tears to the 150 000 visitors a year who visit this shrine to the horrific events that scarred Rwanda 30 years ago. She was among the 250 000 victims of the genocide who died in the capital city of Kigali alone.

The national death toll was over 800 000.

The victims’ remains are interred in the area of the museum that includes memorials to entire families that lost their lives when roving, heavily armed Hutu soldiers and militia, armed with machetes and other weapons, left a bloody trail of death across the country.

Their victims were mostly Tutsis.

Next to Fillet’s picture is one of Thierry Ishimwe. He was hacked to death with a machete in his mother’s arms.

‘NEVER AGAIN’

Dieudonné Nagiriwubuntu, the manager at the genocide museum, says although the facility has been around since 1999, it was only officially opened in 2004.

He says although being the final resting place for 250 000 victims of the genocide, it also serves as a place of education, “as a place to understand more how genocide was planned, executed and the precipice the country faced”.

“And also about some of the solutions that were shared by the good leadership to restore peace and reconciliation in Rwanda.”

He says the national archive not only shares the stories of victims, but also perpetrators who had asked for forgiveness.

The museum is a cornerstone of peace and the values of education, which are imprinted on the minds of the young through the ministry of education “to make the ‘never again’ part of our community”, Nagiriwubuntu says.

These values include empathy, critical thinking, responsibility and trust so that the country makes sure ‘never again’ remains Rwanda’s reality.

Inside the museum, tour guide Maurice Kwizerimana returns to the gruesome death of Filette.

He says her parents were killed on the same day in 1994.

He says in some cases where children were killed during the genocide, the attackers would take their clothes and formula milk to feed their own children.

About Thierry’s death, Nagiriwubuntu says: “Here was someone who was nine months old, a person who doesn’t know skin colour or the region they lived in, or whether they are Christian or Muslim. They don’t know how to talk, to speak.”

He says Thierry’s mom was also killed with machetes after her son was murdered.

“That truly defines what we call genocide.”

In the dimly lit corridors where the child victims’ photographs and inscriptions are displayed, five-year-old Patrick Shimirwa’s inscription reads that his favourite pastime was riding his bicycle.

His favourite foods were chips, meat and eggs. His best friend was his sister, Alliane. He was a quiet and well-behaved boy who was hacked to death with a machete.

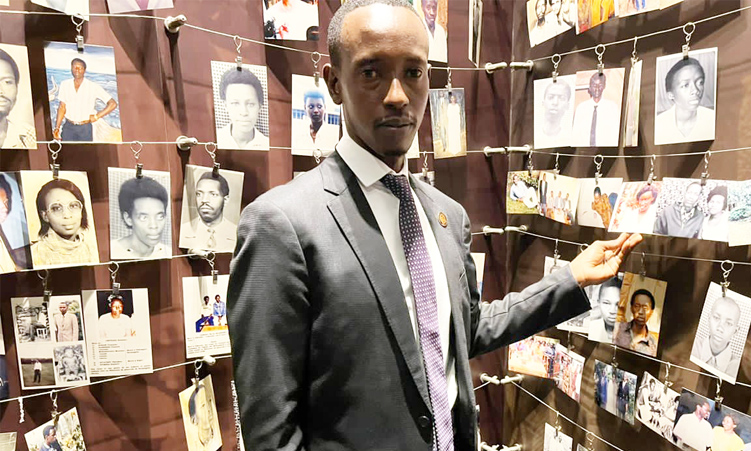

WIPED OUT … The Imena family in Kigali was one of the 15 000 families in Rwanda that were destroyed during the 1994 genocide in the country. These families comprised 68 000 people.

THE WORLD FAILED RWANDA

David Mugiraneza loved football and enjoyed making people laugh. His dream was to become a doctor.

His last words before he was tortured to death were: “Unamir (the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda) will come for us.”

Ghanian diplomat Kofi Annan, who died in August 2018, was the United Nations (UN) peacekeeping chief at the time of the 1994 genocide.

In 1994, the UN instructed Canadian lieutenant general Romeo Dallaire, who headed the UN peacekeeping force in Rwanda, not to intervene.

Dallaire wanted more troops to quell the escalating violence, but instead most of them were withdrawn.

In 2014, Dallaire wrote in a Washington Post column that “preventing this genocide was possible; it was our moral obligation.

And it’s a failure that has haunted me every day for the last 20 years”.

Annan acknowledged the UN’s shortcomings, saying “the world has failed Rwanda at that time of evil” in Kigali in 1998.

At the time Annan had already taken up the reins as UN secretary general, a post he held from 1997 to 2006.

Kwizerimana says the failure of the UN had devastating effects on Rwanda as he enters another area of the genocide museum where the walls are lined with photos of the victims of the slaughter in Kigali.

The pictures were sourced from family members who had them before the genocide, or who got them from their belongings.

Many of the photographs are from identity documents.

Others are photos of special moments, when someone bought a car, or got married.

GENOCIDE

The Rwandan genocide, or genocide against the Tutsi, took place from 7 April to 15 July 1994 sparking conflict and the subsequent slaughter.

Over approximately 100 days, armed Hutu militias targeted the Tutsi minority, along with some moderate Hutu and Twa individuals.

While the official Rwandan Constitution suggests a death toll exceeding one million, scholarly estimates indicate that around 500 000 to 800 000 Tutsis were killed.

The conflict originated in 1990 when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group primarily comprising Tutsi refugees, invaded northern Rwanda from Uganda.

Despite the signing of the Arusha Accords in 1993 between the Rwandan government, led by Hutu president Juvénal Habyarimana, and the RPF, the assassination of Habyarimana on 6 April 1994 disrupted the peace accords and created a power vacuum.

Genocidal acts began the following day, with the majority Hutu forces targeting key Tutsi and moderate Hutu figures.

The shocking scale and brutality of the Rwandan genocide elicited worldwide dismay, yet no country took decisive action to halt the killings.

The majority of victims met their tragic end in their own villages or towns, often at the hands of their neighbours and fellow villagers.

Hutu gangs actively sought out victims who were hiding in churches and school buildings, employing machetes and rifles to carry out mass murders.

Additionally, the genocide was marked by pervasive sexual violence, with an estimated 250 000 to 500 000 women subjected to rape.

The lack of international intervention during this period allowed the atrocities to unfold unchecked, leaving a lasting impact on the collective consciousness of the global community.

SKULLS

Although visitors to the genocide museum are not normally allowed to take photographs, special permission was granted to reporters from Namibia and other countries, including Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya, to photograph parts of the facility.

However, among the sections that were off -imits to reporters was a room in which the skeletal remains of some of the victims, including skulls, were housed.

Kwizerimana says this is because of strong cultural beliefs around displaying the remains of the dead.

He says the museum is one of 200 memorials across the country, many of which are churches which had previously been safe for Tutsis, but became areas they were herded to to be slaughtered during the genocide.

As the tour group leaves the museum, they pause at a photograph of four-year-old Ariane Umutoni.

Her favourite food was cake, and she loved singing and dancing.

Cause of death: “Stabbed in the eyes and head.”

Another one of the estimated over 95 000 child victims of the Rwanda genocide.

- During the commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the genocide, The Namibian and various African media outlets are attending what is known as ‘Umushykirano’, which is an annual forum for national dialogue provided for by the constitution of Rwanda.

- During the event, Rwandans gather to assess issues related to the state of the nation and national unity, among others.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!