Namibia only has one outdated machine that treats cancer through radiation at a public health centre, oncologist Dr Pelagia Peggy Emvula said, warning that this contributes to delays in treatment for state patients.

“Patients at private centres get better treatment because they can get their hands on anything, subject to them paying. The machines that they have, have higher energy levels than ours. As such, it takes a long time to treat one patient, sometimes from 30 to 45 minutes,” Emvula said on Desert Radio last Thursday.

The discussion included former health minister Dr Bernard Haufiku and Cancer Association of Namibia (CAN) chief executive Rolf Hansen.

“What is happening at the moment … we send about 80% of our patients for private treatment, and the government has to pay,” Emvula said.

The radio programme addressed the detrimental impacts of cancer stigma and explored the potential positive outcomes associated with public figures like president Hage Geingob openly disclosing their cancer diagnoses.

According to Emvula, there’s only one machine in all of Namibia’s public healthcare centres used for cancer treatment, and it’s getting old.

This machine, called a Cobalt 60 radiation machine, uses strong rays to fight cancer.

She said the current machine has outlived its lifespan – pending the importation of a new one in March this year.

Haufiku said with the line of cancer patients growing ever longer, the country continues to limp without a linear accelerator, a standard treatment machine for all forms of cancer.

Haufiku said while the government’s efforts towards cancer treatment, which entail the bankrolling of public patients at private health establishments, are commendable, this money could be better used to procure new machines and the latest chemotherapy medicine.

OBSOLETE MACHINES, SHORT-STAFFED

“The Cobalt 60 machine has a problem due to the fact that the source has extended its life cycle. We are waiting for a new source, which will probably come in March this year. But this is the 10th year, which makes it double the life,” Emvula said.

She said with only three radiographers to operate the machines, including one that treats cervical cancer, the state is severely short-staffed.

“Looking at these aspects, we are clearly not where we are supposed to be.”

When it comes to chemotherapy, Emvula said most of the drugs are available from the state, however, newer drugs, like for immunotherapy, are sometimes in short supply.

“It is a problem, because that money could have helped with the purchasing of new machines or some of the medication that we experience shortages of during chemotherapy,” Emvula said.

Haufiku emphasised the importance of building capacity for the state in order to remove its dependence on the private sector.

“We have to build capacity in such a way that whenever people need treatment, including palliative care, they get that treatment. When you look at cancer for example, with all the resources that are available and the state is paying for, most of that is catered for only in the private sector at a commercial rate,” Haufiku said.

He said one cannot talk about having capacity when there are only two private health centres taking care of all cancer patients.

“Up until now, the state does not have a linear accelerator, which is the standard machine for treating most cancers. That already says something. And these are the things that we need to put up, not only in Windhoek, but outside as well, to avoid having patients travelling from especially the northern parts of Namibia, sleeping on the floors in hospitals, before the lucky ones can get to the available machines,” Haufiku said.

Also referred to as Linac, a linear accelerator, is a machine that aims radiation at cancer tumours with pinpoint accuracy, sparing nearby healthy tissue.

BACKLOG

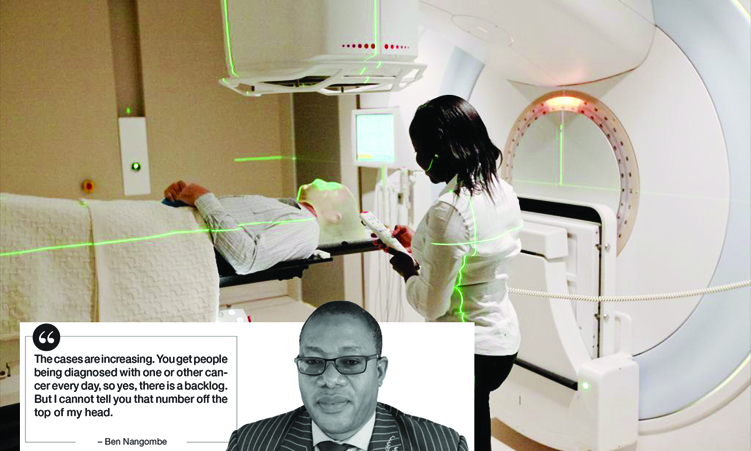

Health executive director Ben Nangombe confirmed that there is a backlog in cancer treatment as a result of the outdated, single Cobalt 60 radiation machine.

“The cases are increasing. You get people being diagnosed with one or other cancer every day, so yes, there is a backlog. But I cannot tell you that number off the top of my head,” he said.

Nangombe confirmed that the source that the machine uses has gone past its lifespan and as a result, a new source has been ordered, which is yet to be delivered.

“It was to come in December last year but there were challenges with the supplier who is based in Canada. As a result, we currently refer our patients to private health facilities for treatment,” Nangombe said.

“This costs the government between N$95 000 and N$150 000 per patient, depending on their conditions, even though in some cases the price comes down to N$60 000,” said Nangombe.

He further confirmed that the government is yet to have the linear accelerator which is a machine used in conjunction with other machines such as the simulator to make cancer treatment easier.

“It is very expensive, but we have ordered it. It is part of our investment in making sure that cancer treatment is improved in Namibia. Technology is evolving and so should we,” he added.

LACK OF CAPACITY

The discussion comes as Geingob undergoes treatment in the United States of America, following his cancer diagnosis earlier this month.

The trip has raised questions on whether Namibia’s healthcare system is not good enough for the treatment of the head of state.

Hansen said cancer patients have the right to information, as well as to decide with the doctors what the best treatment option could be and where to get it.

“Ours is to disclose all information to the patient and for the patient to then decide on which treatment they prefer based on the affordability aspect of course.”

Hansen said the oncology sphere in Namibia has developed very progressively in the last decade, particularly through the emergence of private oncology units, such as the one at the central hospital.

He added that Geingob’s decision to go abroad for treatment may have stemmed from the diagnosis and prognosis of the disease, however, from a communications point of view, it may fuel doubts as to whether Namibia’s healthcare system is not good enough for the head of state.

“The reality is that our healthcare system is struggling, especially the state oncology section. I am the head of the cancer association and as such, the voice of the patients and I have to lobby that we must do better for our patients.

“That there is a huge lack in our healthcare system is a reality and I think the masses feel that if it is not good enough for the head of state, why should it be good enough for the masses.

“That is the question that we all need to discuss. If the answer is that it is because the best possible treatment is not available in our country, it makes sense because we have a lot of Namibians that go to South Africa, Switzerland, Germany and the US.”

“I think it is a matter of clarification as to whether or not treatment can be done here and if not, why our treatment – whether state or private – is not good enough,” he said.

DEALING WITH STIGMA

Haufiku said Geingob is not spared from the stigma associated with cancer patients.

He described stigma as “some kind of psychological illness found in uninformed and ignorant people”.

“It is mostly based on irrational fear and the false feeling that one person is better than another.”

Haufiku said what is lacking is knowledge and the impartation thereof should be a good starting point.

“We have had a huge problem with HIV. [So] for us in the public health domain, having someone disclose the state of their health openly serves as a good awareness raising campaign. Nowadays, cancer only kills people because of a lack of awareness.

“Many people think, having cancer means they have done something wrong. And the head of state coming out is encouraging,” Emvula said.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!