In June 2029, the Namibian government pays N$200 000 to 500 000 households from oil tax revenue. Desperate to win elections later that year, the ruling party raids the sovereign wealth fund and mortgages future oil revenue to afford the N$100 billion payout.

Such a scenario is not hard to imagine considering that now, in 2023, the government appears all over the place, hosting oil and gas talk shows but with barely any concrete plans on how to ensure Namibians benefit optimally if and when the country can export oil.

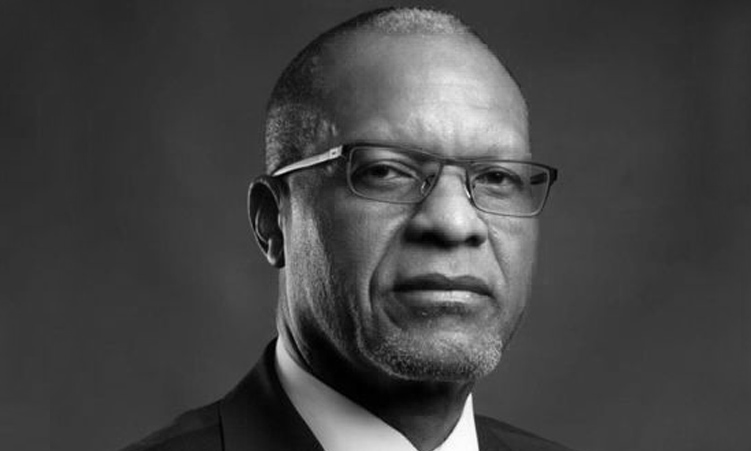

“Poor management of the oil and gas sector can drive corruption and inequality that in turn will fuel social tensions and threaten political stability. We thus need to learn lessons from some oil-producing nations…” energy minister Tom Alweendo told a conference this week.

Judging by what Alweendo and several top bureaucrats responsible for regulating the industry said at the conference, the country has a long way to go in terms of putting in place measures that will result in broad-based benefits for the population.

The oil and gas conferences are attracting large numbers – 700 this week – in contrast to another about inequality which barely got key policymakers to pay attention.

Huge policy gaps exist and it’s not clear what Alweendo and the government are doing to ensure that Namibia’s highly anticipated oil industry helps narrow inequality.

Nor are there plans to avoid Namibia falling prey to curses like Dutch Disease, whereby the discovery and dominance of one natural resource leads to other industries collapsing.

Officials talk about diversifying the Namibian economy, yet how that will be done, no one seems to know.

If anything, we could witness a continued bulging of government jobs and parastatals with politicians and their cronies benefiting from the offshoots of contracts from the oil business.

At best, the oil will remain under the ocean if major oil companies remain sceptical of committing to massive investments amid uncertainty over laws and the potential for the kind of corruption experienced in countries like Angola, Nigeria, Russia and Venezuela.

At worst, Namibia might attract investors who don’t care about paying bribes because they operate in countries like Brazil, China and Russia, where laws have not caught up with good governance and money-laundering instruments.

If we have been unable to get investment laws functioning for nearly a decade, how will Namibia ensure local participation in the sophisticated global oil industry?

Officials are clearly fighting each other for control, but what is not clear is what they want to put in place.

So which way is Namibia likely to go? Norway would be the ideal template to follow. While not desirable, most Namibians can likely make peace with the examples of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Worryingly, the current lack of clarity suggests Namibia will end up with an oil industry looking like Angola and Nigeria.

We are running out of time.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!