Whenever Elizabeth Thindhimba closes her eyes, she sees the crocodile that took her nine-year-old daughter.

Thindhimba has been having these recurring nightmares for weeks.

Her daughter Justine called out to her that day. She still remembers her terrified screams.

“She screamed, ‘Mama,’ and I couldn’t help her. That’s all that is replaying in my mind day and night. I cannot sleep. I don’t have her body to bury,” she says.

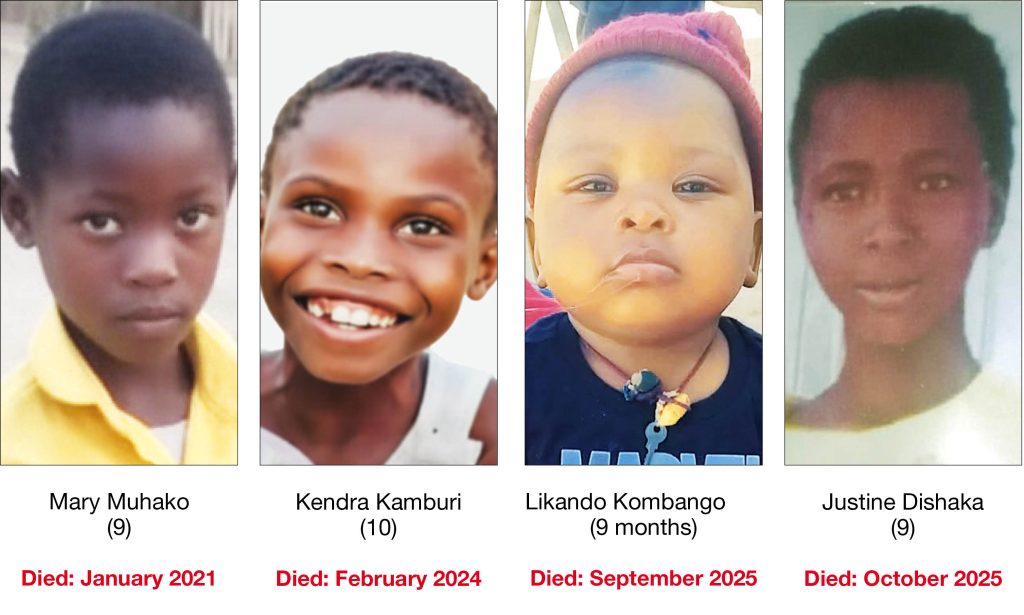

Since 2021, more than five children, including Justine, have been attacked by crocodiles in the Kavango River. None of their bodies have been recovered.

On Saturday morning, 25 October, Justine accompanied her parents and twin brothers down to the Kavango River at Kamutjonga village in the Mukwe constituency to wash clothes.

Justine, a Grade 3 pupil, was washing her school uniform before classes on Monday. The family do their laundry at the river since, as they do not have running water at home.

At around midday, Thindhimba was folding their laundry in bags when she turned and heard her daughter’s deafening screams.

“I saw a huge crocodile coming out of the river, grab Justine by the legs, and pull her into the water. I was paralysed with shock. I just stood there,” Thindhimba recalls.

Justine’s father, Christoph Thindhimba, who was closeby with the other children immediately started rushing towards them when he heard her scream.

“THE CROCODILE TOOK JUSTINE”

Thindhimba says Christoph tried to jump into the river to save her. “I stopped him. I knew it was too late,” she recalls.

Thindhimba says she sat by the riverside, and cried for hours on end. The afternoon of 25 October was the last time she saw her little girl alive.

Her body was never retrieved, and the authorities had stopped searching.

DREAMS CUT SHORT

Justine’s uncle, Frans Thikusho, recalls that she could not stop talking about how she wanted to become a nurse when she finished school.

He says two days before the river took her, she came to him to ask him to buy her a new school uniform for next year.

“I knew that school was always her priority. She really had a bright future ahead,” he says.

Thikusho says Justine’s parents have been struggling to come to terms with their loss.

“If we could afford it, we could have paid for them to seek professional help. We’ve stopped the other children from going to the river,” he says.

The crocodile has since been tracked down and killed. On 6 November the police called the family to identify items found in its digestive system, including bones and teeth.

Justine’s father and several of her uncles, positively identified the clothing – navy blue shorts – retrieved from the animal as being Justine’s.

NOT THE ONLY VICTIM

Justine is not the only child to fall victim to the crocodiles of the Kavango River.

On 29 September a nine-month-old boy from Kamutjonga village, Likando Kombango, was snatched from his mother’s arms. His remains have not been found.

Likando’s mother, Annastasia Nyiru (24), fell when a crocodile bit her. At that point, the baby was taken.

“I feel like I am losing my mind,” Nyiru says. “My sweet little boy that made me laugh is gone. I will never get over this loss,” she tells The Namibian.

Officials from the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, who put down the crocodile, believe it to be the same animal that took Justine.

Nyiru and Thindhimba are hopeful that after the DNA testing and identification of the bones and teeth retrieved from the crocodile, they will have something to bury.

A MEMORIAL SERVICE WITHOUT A BODY

Rosa Karakandje has no hope of burying the body of her daughter and only child, Mary Muhako (9), whom she last saw on 26 January 2021 after a crocodile claimed her near Ndongo village.

Mary had followed her great-aunt to the Kavango River after school.

“All I have is a death certificate that was issued without a body. We hosted a memorial service in hopes that her body would be recovered,” she says.

At Bagani village, Patricia Thindhimba, too, has not been able to bury her daughter Kendra Kamburi (10), whose body was not found after a crocodile attack along the Kavango River on 27 February last year.

“But, I never got to where I was going because while still on the way, I received the worst news of my life. I couldn’t believe it then and even until now. My daughter is gone without a trace, no remains, no death certificate. Whenever I think of her and the way she was taken away from me, I find myself crying,” she says.

Another Bagani village resident, Mushinga Kashamba, did not have the chance to give her daughter, Kasiku Shighongedi (7), a proper burial because her body was never found.

Kashamba says Kasiku went with her grandmother to fetch water in the afternoon when she was attacked by a crocodile at the Kavango River on 26 November 2020.

FAMILIES LEFT TO PICK UP PIECES

Mukwe constituency’s community activist, Aron Mundanya, says the police and environment ministry officials take statements from victims of human-wildlife conflict incidents, but do not take the cases further.

He adds that victims are left to deal with the trauma on their own without counseling or compensation from the government.

There are an estimated 11 000 crocodiles in the Kavango River.

Outgoing Mukwe constituency councillor Damian Maghambayi says he, too, needs counseling after what he has witnessed and heard about crocodile attacks in the river over the years.

He adds that the animals have now started attacking people alongside the river.

He adds that there is an urgent need for more boreholes to be drilled closer to these communities.

“At present there are no community awareness campaigns in areas prone to crocodile attacks. The environment officials are only seen after an attack,” he says.

“The river’s dangers are not known until it’s too late. Community-based incentive programmes should be implemented to work with the environment ministry to combat human-wildlife conflict.”

Maghambayi says the death of Ellen Diisho (15) in 2022 in a crocodile attack prompted the Kavango East Regional Council to construct a water pumping and purification project at Thikanduko village.

As a result, the crocodile attacks have been minimised in that area, suggesting that the ministry should look into funding such projects more widely in areas prone to attacks.

WAITING FOR DNA RESULTS

Kavango East police crime investigations coordinator Bonifatius Kanyetu this week said the human remains recovered from the crocodile, which could be those of Justine and Likando, have been sent for DNA testing.

“We are waiting on the DNA results to find out if it’s truly their bones,” he said.

Kanyetu said he has to scrutnise inquest dockets to confirm facts on Mary, Kendra, and Kasiku.

Most bodies have, however, not been retrieved following crocodile attacks at Mukwe, he said.

“There is an inquest backlog dating back to 1999 of bodies that were not retrieved. Some of the inquest dockets are even lost, although we have the serial numbers.

“Currently, I am working with five families who have taken their case to the High Court for their loved ones, whose bodies have not been found, to be declared dead,” he said.

Kanyetu said the Inquest Act 6 of 1993 should be amended, because it only declares individuals dead immediately upon being lost at sea, but does not include rivers.

“Many families are suffering since their loved ones cannot be declared dead due to a lack of remains. Then the pension schemes do not want to pay out,” he said.

MITIGATING MEASURES

Ministry of Environment and Tourism spokesperson Ndeshipanda Hamunyela says to minimise crocodile attacks, they have drilled boreholes at various villages within the Mukwe constituency.

“In addition, a crocodile enclosure was also constructed near Popa Falls and at Muitjiku to manage crocodile movement and reduce encounters with community members.”

“We will engage the water point committee to support them with additional water tanks to ensure enough water for the village,” she says.

She says compensation is only given after investigations are concluded and documents such as a death certificate confirming the victim’s identity have been submitted.

“Offset payments are also processed based on the circumstances surrounding each incident, including what the affected person was doing at the time,” she says.

She adds that they constantly advise the community to pack thorn bushes at inlets on the river to keep crocodiles away, a practice that has been in use for generations.

In an age of information overload, Sunrise is The Namibian’s morning briefing, delivered at 6h00 from Monday to Friday. It offers a curated rundown of the most important stories from the past 24 hours – occasionally with a light, witty touch. It’s an essential way to stay informed. Subscribe and join our newsletter community.

The Namibian uses AI tools to assist with improved quality, accuracy and efficiency, while maintaining editorial oversight and journalistic integrity.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!