A part of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act, under which assets belonging to six of the men charged in the Fishrot fishing quotas corruption and fraud case have been placed under a property restraint order, violates the constitutional rights to be presumed innocent until proven guilty and for the protection of property, a lawyer argued in the Windhoek High Court yesterday.

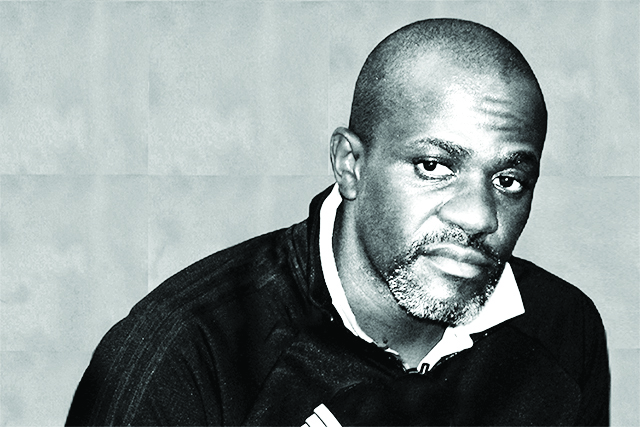

The argument was made by South African senior counsel Vas Soni, representing Fishrot accused James Hatuikulipi, during the hearing of an application by Hatuikulipi to have a part of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act declared unconstitutional.

Judges Shafimana Ueitele and Herman Oosthuizen and acting judge Collins Parker, who heard oral arguments on Hatuikulipi’s attack on the law from Soni and senior counsel Wim Trengove, who represented the prosecutor general, attorney general and minister of justice, reserved their judgement at the end of the hearing. Ueitele said the court will attempt to deliver its judgement by 17 October.

Hatuikulipi is asking the court to declare as unconstitutional a part of the act that states the High Court must grant a property restraint order if it “appears to the court that there are reasonable grounds for believing that a confiscation order may be made” against a person facing charges in criminal proceedings that have not yet been finalised.

He is also asking the court to declare that a property restraint order granted in November 2020 in respect of assets belonging to himself, five co-accused in the Fishrot case – former attorney general and justice minister Sacky Shanghala, former minister of fisheries and marine resources Bernhard Esau, Hatuikulipi’s cousin Tamson Hatuikulipi, Ricardo Gustavo and Pius Mwatelulo – and 10 corporate entities or trusts under their control is unconstitutional, and to set aside that order.

The restrained assets include bank and investment accounts, interests in companies and close corporations, immovable properties, nearly 60 motor vehicles, firearms, jewellery and several luxury watches.

In terms of the restraint order, which is due to remain in place until the men’s pending criminal trial in the Windhoek High Court has been concluded, the affected assets may not be dealt with by anybody, must be preserved and have been placed under the control of two curators.

The act states that a court may order the confiscation of assets under restraint after the owner has been convicted of an offence and the court has determined the value of the benefit the owner derived from the offence.

Hatuikulipi says, in an affidavit filed at the High Court in July last year, that the act’s requirement that there should be reasonable grounds to believe a confiscation order may be granted before a court issues a property restraint order means a court would have to first conclude there are reasonable grounds to believe he would be convicted.

The effect of that requirement in the law is that his constitutional right to be presumed innocent is limited, Hatuikulipi claims.

He is also claiming that the restraint order granted by the court in November 2020 limits his constitutional right to own and dispose of property.

Soni argued that the section of the act that Hatuikulipi wants to be declared unconstitutional requires from a court to obliterate the presumption of innocence from its mind.

It is also “unfair, disproportionate and arbitrary” that the act does not say the value of assets covered by a restraint order should be proportionate to the value of the benefit the owner is alleged to have received from unlawful activities, Soni argued. Trengove argued that if the part of the act targeted by Hatuikulipi is struck from the law, the act would say that a restraint order can only be made when a confiscation order has been given, after an accused person or entity has been convicted.

At that stage of legal proceedings a restraint order would be pointless, he said in written arguments filed at the court. Hatuikulipi’s “attack would in other words do away with restraint orders altogether”, which would substantially undermine the entire system of asset forfeiture under the Prevention of Organised Crime Act, Trengove added.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!