In a country where words have lost much of their meaning, Namibians will once again vote for their preferred parties and candidates in the upcoming elections.

Every political party and candidate contributes to their own myths, and the governing party, Swapo is more energetic than most in its cultivation.

The uncomfortable truth must be told: As a first generation national liberation movement, Swapo has been successful in capturing the state and making public resources accessible to some.

Ultimately, it has been a matter of roses for the few and thorns for the many. The reasons for this are important to grasp.

STATE CAPTURE

The defining features of most first generation national liberation movements such as Swapo have been their armed resistance to colonial rule, anti-colonial nationalism as their ideological mantra, and state capture as their first strategic objective after they were elected to power.

Without exception, national liberation movements have been amorphous, comprised of a matrix of different ethnic and social classes.

In important respects, they have been undemocratic and intolerant of opposition.

To a varying degree, they’ve relied on coercive practices and cooptation to maintain their hegemony.

They are good at making generous promises to citizens after assuming power and advance a strong redistributive agenda under the leadership of a founding personality.

It is the hybridity of such movements that partly explains their initial success and their ultimate unravelling.

DOMINANT MODES

In the context of southern Africa, there have been two dominant modes of transition from liberation to governing party.

These are: The privatisation of liberation – claiming an exclusive role for one party in bringing about ‘liberation’, and corporatised liberation – forging an elite pact between older business and technocratic elites and the incoming political elite.

Examples of the former include the MPLA in Angola, Frelimo in Mozambique and Zanu-PF in Zimbabwe.

Swapo and the ANC fall in the second category of corporatised liberation.

A hallmark of both categories of liberation politics is the tendency to conflate the party and the state. Creating, over time, party states.

PUBLIC POWER VS GOVERNANCE

Liberation movements tend to confuse power with governance.

The first, ‘power’, is relational and implies an element of control.

The second, ‘governance’, is about core democratic values such as accountability, transparency, justice, fairness and responsiveness to a diversity of interests and needs.

In the case of Namibia, apartheid and the more recent liberation struggle left serious democratic deficits in their wake.

Governance does not come naturally to those who govern. Namibia somehow owned it to the politically connected to make their fortune.

This folie de grandeur was instant and incurable.

Since independence, we have witnessed a few alarming examples of the condition, with the new elite having no strong aversion to rank and status.

In retrospect, Namibia had the good fortune to have a small population in a sizeable space, inherited meaningful physical infrastructure from the departing neo-colonial power and elements of a functioning state.

The state inherited insignificant public debt, while a coterie of technocrats trained in exile, largely by the former United Nations Institute for Namibia (Unin) and at reputable universities, provided the technical know-how of how to manage the state.

Moreover, a modern liberal Constitution and the pre-eminence of the political over the military leadership when Swapo took power oiled a smooth transition.

International goodwill and solidarity anointed a highly symbolic transition from war to peace. from apartheid to representative democracy.

Small as it was, and still is, civil society – with its free, pluralistic media, supported by the rule of law – provided a counter-balance to a dominant party.

SELF-SATISFACTION

While Swapo politicians and hopefuls give off waves of well-fed satisfaction and the moneyed classes live in salubrious suburbs, all is not well in the ‘Land of the Brave’.

The levels of looting are unsustainably high.

Multidimensional poverty infests the social and spatial economy of the country.

Inequality cuts deep into the fabric of society.

There is a visceral precarity in the villages, informal settlements, towns and cities, calling for ‘security’, ‘peace’ and ‘development’.

For inhabitants of gated estates, ‘lifestyle complexes’ or ‘security villages’, it is the colour of your money, not of your skin, that counts.

Ministers from the distant capital continue to make unfulfilled promises to the electorate.

Manifestos ring hollow in a country where racial and social divides are deeper than ever for words have lost their meaning.

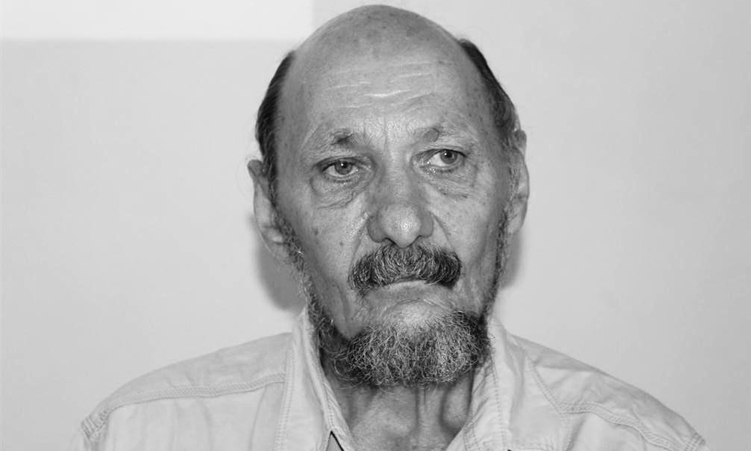

- * André du Pisani is emeritus professor of politics at the University of Namibia (Unam).

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!